The “Seven Fields of Practice” – Contemporary Steiner Special Needs Education - The post-digital curriculum of Ruskin Mill Trust

Dear colleagues,

In his book “The age of spiritual machines” Ray Kurzweil predicts that by the year 2029 discussions around the rights of artificial intelligences will be held, most people will have neural implants and some machines claim to be conscious with the claims largely being accepted. By the year 2099 he predicts that consciousness does not have to have carbon- based hardware (brain) but can exist freely on machine supported servers, people without neural implants are not able to meaningful socially interact and the question of living forever has been answered as carbon based bodies are no longer essential. This book is already 20 years old.

Depending on what your starting point is some of you live more in their thinking and might think “cogito, ergo sum”. Others live more in their feeling life and connect to the world through this and again others live very much in the will.

All three are gates to the other and the world as well as to ourselves and ideally we cultivate all three of them and can use them to make the world a better place.

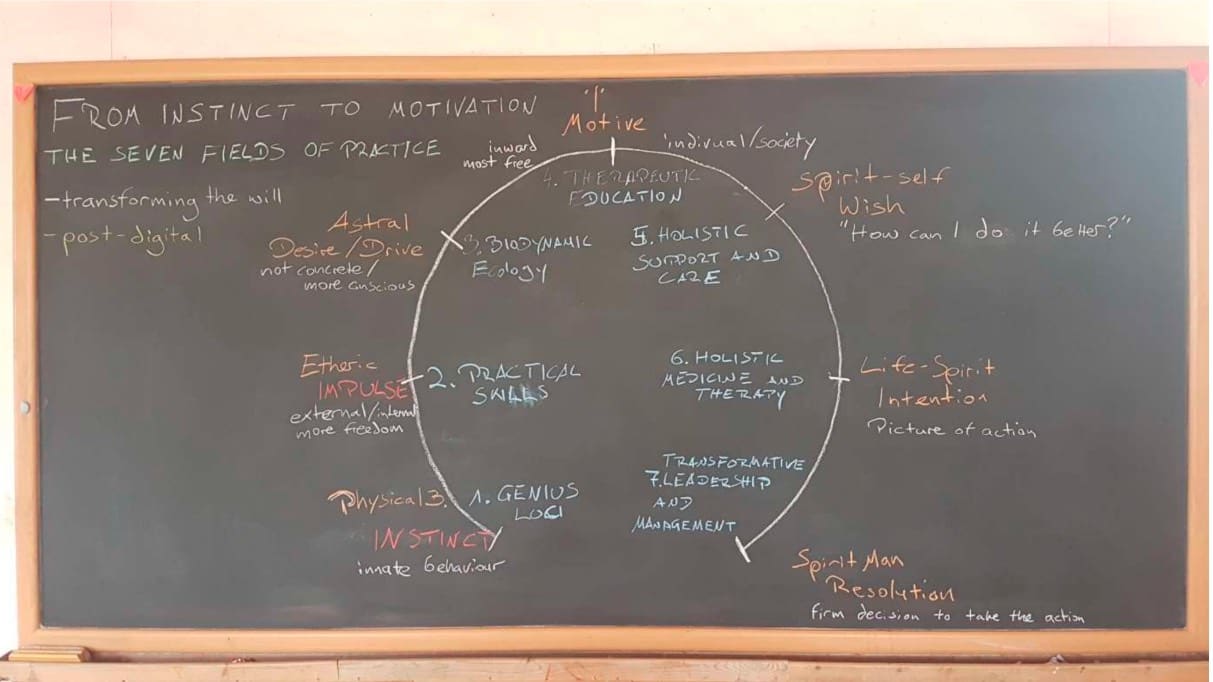

I want to explore with you the role of the will and how crafts are used in Ruskin Mill Trust as a vehicle of transforming the will from instinct to motivation. Rudolf Steiner beautifully described this in the fourth lecture of “The Study of Man”. However, I do not want to leave this just as a theoretical treatise but rather want to place this into context. In Ruskin Mill the crafts are based as a vehicle for transformation into a context which we call “The Seven Fields of Practice”.

Steiner describes that the will in its crudest form could be described as instinct. This is very much related to the physical body and it is what is usually described in science as fixed action pattern (FAP). It is hard-wired and not learned behaviour. It is a given and the explanation why beavers build dams, why birds have sometimes very elaborate dances when mating and why some moths fall straight to the ground when perceiving a certain ultrasound which resembles that of a bat. There is no choice, no freedom, it just has to happen. It is immediate, following an external sensory stimulus. With most animals, e.g. the beaver, it goes as far as shaping their physical bodies, which means the environment and the animal become part of the same dynamic, two sides of the same coin. Beavers would indeed find it very difficult not to cut up trees and build dams but decide to do something else, for example build nests in trees. Interestingly, science struggles to clearly identify instinctual responses in man beyond some very early behaviours of the newborn that are also lost in the first few months. After that the human body is fairly unspecialised and free.

The student and the staff journey in Ruskin Mill starts in field 1 with what we call the Genius Loci. In this we try to explore the location usually with a team of staff, we explore the geology, the mineral kingdom, the plant world, the animal kingdom and the human history that was or is alive in the place. It is what Goethe called “Anschauung”, a “delicate empiricism”. “The phenomenon is not detached from the observer, but intertwined and involved with him.” —Goethe (1998, p. 155, Maxim 1224).

It is difficult to explain what is actually happening in such a Genius Loci audit as there are effects far beyond the mere intellectual “knowing”. Something happens between the staff team, the individual and the place as well as everything that inhabits the place. It does create an immediate connection, opens up a conversation with the place. This is in the context of a time of loss of connection, where we are not connected to the people we are with, the things we use and do, the times we do this and the food we eat. Autism, shift work, the digital world and Mc Donald’s are only signatures of this what we all experience to a greater or lesser extent.

I do not want to suggest that through a Genius Loci audit the staff team achieve an instinctual connection with the place but just want to emphasise that through this conscious process which sometimes lasts over months a more immediate connection, or re- connection is achieved, which carries future decisions, ventures and actions on a level which is helpful and not always conscious or appreciated enough. I can also highly recommend going through this process together with the staff team when an organisation is struggling and has to make the double that lives in the location conscious in order to work with it.

In a Goethean observation of what is alive in the location one can start to perceive the will on the level of instinct in the different forms of animals which are present in the location. As Steiner says in the fourth lecture of the Study of Man: “If we study all the different species of animals as distributed in the world we shall find that the forms of their physical bodies always give us the clue to the study of the different kinds of instinct.” Man can see outside what is present in him to some extent. But there is more happening where man and in our case the whole staff team –sometimes unbeknown to themselves- enter a conversation with the elemental world and the angelic realm of the place. The exact effects of this would need further spiritual scientific research which unfortunately is beyond the scope of this introductory talk as well as my own current capacity.

Out of the audit of the location we then develop the craft curriculum for the centre. This is field 2: Practical Skills. Again, this means that the student experiences inherent connectedness as the materials which are used in the craft are often derived from the location. In an act of human will, the material is lifted from the unconscious state in the location to a more conscious state as you start working with the material. Therefore, the student uses his or her will to literally lift the material into a more conscious state, in the process already transforming the material but more importantly transforming himself in the experience of the origin of the material.

Steiner gave the picture that as the etheric body permeates the physical body it takes hold of what in the physical body manifests as instinct. Then instinct becomes “impulse” or “drive”. The distinction between the terms “instinct”, “impulse” and “drive” are not always very clear in modern psychology and different people use it with slightly different meaning. However, one can possibly see that when moving from “instinct” to “impulse” there is a small opening and a very small window of freedom comes in where the response to the stimulus does not have to be automatic and instantaneous. Some more consciousness comes in, also the stimulus does not have to be external necessarily but can be internal while still largely based on the physical, like hunger, thirst, sexual drive.

There again is really a lot of possibility for research, sensible and super-sensible, of how the will is engaging in transforming the material in the craft activity. Building on the experience of field one where we discover our instincts out there and our connectedness with the world, it is now a feasible question how through the crafts we transform our impulses. The work with animal material as in wool, plant material as in wood and mineral material as in clay clearly does have a different quality to it and the human will is applied in different ways. How to apply one’s will can possibly best be experienced in the polarity of working with wool in felting which has more a dreamlike quality, round movements, warm soapy water, nice scents – and then iron age forging. In iron-age forging the metal has to be heated to a certain temperature and there is only a very short window of a few seconds to hit the metal in a very specific way – the archetype of bringing a will impulse out of the infinite possibilities into the reality of time and space. What we call “bringing something to the point”.

By meeting the resistance of the different materials in this “descend into matter” the will impulses used are changed and modified according to the lawfulness of the material. The therapeutic value of the crafts then lies in the repetition of actions that is needed and therefore the adjusting effect it has on the life of impulses or the etheric life. Therefore, to follow this line of thoughts further, one could possibly say as the landscape of animals in a location is a picture of the instincts which are there, the landscape of the crafts is a picture of the different impulses which are possible. While the list of research questions already at this point is virtually inexhaustible the good news is that the relationship of crafts to impulses and our etheric body is very accessible to our own conscious experience when we engage in crafts. So by the end of this conference certainly all of those who are booked on the practical workshops will have more answers to these questions. This relationship is also one of the areas of continuous research, one example is the research that is going on around brain plasticity for example as summarised by Norman Doitsch (Plasticity of the Brain) or Sennett (the craftsman). Ruskin Mill Trust has also commissioned its own research with Aric Sigman “Practically Minded” and within its Masters programme which has now been going for four years, several Masters have addressed already the question between the resistance that the materials provide and the transformation the young person goes through by transforming the material.

Now, if we were to bring even more consciousness into the human will and see it moving more away from the external world into the inner world we would come to what is called “desire”. It is remarkable that where modern psychology still struggles to distinguish between the scientific definition and meaning of instinct, impulse, drive and desire Steiner describes it remarkably clear in a way that is accessible to diligent observation of the own soul life and experience. He describes impulse as “a thing which manifests in a uniform manner from birth to old age; while desire is something [...] which is created afresh by the soul every time.” When man’s sentient or astral body takes hold of the etheric and physical body and lifts impulse and instinct into consciousness and moves them more inward, desire arises.

Where do we find the picture of desire in the Ruskin Mill curriculum? It is again in the animals, but this time not in the Goethean observation of the physical shapes of the animals but in the inner life of the animal. Field three: Biodynamic Ecology introduces or re- introduces the animals into the student curriculum with the conscious use of animals. In the one-sidedness of certain animals the student has the opportunity to experience the inner life of another creature in a non-confrontational and objective way, to see the desires come and go, find its fulfilments and see the consequences of satisfying those or delaying gratification. And through this, gaining access to his or her own one-sidedness, inner life, fulfilments or consider delaying gratification-hopefully realising that this is also not the end of the world. The German word “Begierde” has the word “Gier”-“greed” in it. Seeing this greed/desire outside in the animal world in an objective way and seeing that fulfilment only leads to temporary satisfaction puts a certain relativity to it.

When the ego permeates the physical, etheric and astral body it moves the will activity even more into the inner life and lifts instinct, impulse and desire onto the level that is solely human: the motive. The motive is the will as it manifests in the individual human soul and while we find desires in animals we will struggle to find “motives”. Steiner says: “If I know the man's motives, then I know the man.” It is the single human individuality that shines through here powerful in finding his or her motive and motivations.

The truly human we meet in the Ruskin Mill curriculum in field 4: Therapeutic Education which puts an emphasis for the practitioner on Steiner’s insights of human development and the 12 senses. These two key pillars of Steiner’s discoveries act as a lens through which one can enquire the other fields and potentise their efficacy. It is through the –sometimes unconscious but ideally fully conscious- understanding at which stage in their development a student is and what their sensory profile is that a tutor is able to engage one of our complex young people. One could also say that enshrined in the understanding of human phasic development and the sensory profile of a student is what we call “pedagogical skills” of a staff member. Virtually all of our students struggle to engage at least initially as it is a defining characteristic of Ruskin Mill students and reason why they come to us: They could not engage in what was on offer previously. When I advise a staff member who is struggling to engage with a particular student my advice is usually: go back into the history of the student and understand their sensory profile and this usually unlocks something. Engaging a student could also be described as helping the student to find their motivation: “I know why I do something.”

Applying this to a craft item we can make the interesting discovery that craft items –slightly different to works of art- have an inherent purpose. What do we think that is?

Craft items have an inherent purpose that is of a cultural convention. When we take for example a mug out of clay or a spoon, the cultural convention is that instead of drinking water or soup directly from my cupped hands I drink the water from the cup or eat the soup with the spoon. Equally crafted items like a stool, a pair of slippers, a glass, have an inherent purpose which is based on a cultural convention. Therefore, in order to craft one of those items I need to align my own motive with the much larger cultural convention of mankind and society in our time of those items are used. When you think about it there is a significant educational and therapeutic effect in this alignment for young people who are disconnected to be part of the human society and part of their time.

Steiner then describes further how the will manifests differently when the higher –still undeveloped- members of man take hold of it and how they can really only fully do this once man has passed the threshold. He describes how the Spirit Self manifests itself in every act of will when we have a motive as the unspoken and often unconscious wish: “I could have done this better”. Not in order to be a better person but selflessly, in order to perform the act of will better – for the deed. And then how when the Life-Spirit takes hold of this wish it manifests as an intention, a clear –but still unconscious- picture of how we would perform this act of will the next time. Lastly, how, when after death Spirit Man permeates man, this intention as the seed is transformed into the firm resolution to perform the act of will better the next time.

If we wish, one could loosely relate this to the Fields of Practice. In field 5: Holistic Support and Care one could say that the residential staff, the home and the residential side of life, which works a lot with the seven life processes, should very much embrace the unconscious life of the student, be a space to breathe out and allow space for reflection on what has been done during the day and what could be done better. Going further inside one could also say that field 6: Holistic Medicine and Therapies describes how targeted intervention works on the members of the human being from the outside in order to remove obstacles for future development and relate this to the work of the Life-Spirit and the intention being formed for future existences. And one could possibly relate the work of Spirit-Man to take hold of the intention and form a firm resolution for the next earthly existence to field 7: transformative leadership and the importance of resolute and effective decision making in order to manifest change as well as succession planning, accountability, regeneration and self-reflection and research. If I were to talk more about this, I would say that without this last field everything else becomes fragmented, disorganised, incoherent, infertile. Putting it into context of the metamorphosis of the will highlighted for me the importance of coming to “resolutions” at the end of a process in order to affect change and regeneration. This is possibly a field that many organisations need more focus on.

However, I am not going to talk about this. I want to stay with the crafts a moment longer. I invite you to observe this in yourselves over the next days while some of you engage in transforming some materials from the mineral, plant and animal kingdom and through this will transform yourselves. We have followed the journey of the development of the will from the level of instinct which can be observed in the external world in the shapes of animals and experienced lifting of the material (mineral, plant and animal) into a more conscious experience in working with it in the crafts. We have then seen how the experience of the resistance in the different crafts possibly can have an impact on the control of impulses and how this can be helpful in transforming the etheric body.

In the Ruskin Mill curriculum, the student can then observe desires objectively in the external world by experiencing the inner life of other living beings. While working with the materials in the craft process the student is also clearly taming his or her desires as the processes have their own lawfulness that the student is following, hence transforming their astral body. While engaging in the crafts, the student does this with a motive and the mere fact that a student is engaging tells us that the practitioner has been successful in supporting the student to find that motive or motivation in him or herself. This motivation or motive will be aligned in the first instance with higher motivation and cultural convention of the purpose of the craft item. In addition to this the student is likely to add his very own motive as he gives the craft item a future purpose that goes beyond him- or herself as the future use goes beyond the student. Hence, as making the item, you will start thinking about who you are making it for, how it can be of service for the other person...this is no mean feat for a person with for example autism. You will have to think about whether the other person will like it, what are the other person’s preferences etc, in short, while making you continuously practice empathy. Autism research would call it theory of mind. Anthroposophists would call it sense of thought and sense of ego. And these are only the benefits for this life-time.

If we then chose to go further we have learnt that in every act of will that is carried by a motive there is a residue which is the mostly unconscious question: “How can I make it better the next time?” This is the question that anybody who engages in crafts asks him- or herself every-time one finishes an artefact. Is this not the sign how much the ego has been involved and that now -as a seed of the Spirit-Self- this question arises? In craft work we then experience this forming a picture of how to do it better next time and mostly form the resolution to manifest this will the next day!

There is a lot of research now on the benefits of the craft curriculum (see Practically Minded). However, it is important to see that the Ruskin Mill craft curriculum does not stand alone at which point it would only be some form of occupational therapy but it stands in the context of The Seven Fields to create an integrated experience for students. It is exactly this also for the staff, as the farmer, the craft tutor, the therapist learn to work and think together as part of a whole. Beyond this there is possibly still more scope to research how an integrated craft curriculum as a curriculum of the will supports the students to transform their will from instinct to motivation and beyond.

“We live in deeds not years; in thoughts not breaths; in feelings not in figures on a dial. We should count time by heart throbs. He most lives who thinks most, feels the noblest and acts the best.” Aristotle

References:

Doidge, N. (2008). The Brain that changes itself. Penguin Books.Sennet, W. (2009). The craftsman. Penguin Books.

Goethe, J.W. von. (1998). Maxims and reflections. (P. Hutchinson, Ed.). London, Penguin Books.

Kurzweil, R. (2000): The Age of Spiritual Machines. Penguin Books.

Sigman, A. (2015). Practically Minded. RMT commissioned. Freely available on the

website.

Steiner, R. (2004). Study of Man, fourth lecture. Rudolf Steiner Press.